Following the bracing sexual and political candor of “BPM,” writer-director Robin Campillo‘s much-laureled movie about HIV/AIDS activism in Nineties Paris, “Pink Island” initially seems to be a retreat into cozier nostalgia — a toddler’s-eye view of life on a French army base in Seventies Madagascar, flooded with daylight, awash with the fun of youthful exploration. That may appear an obtuse technique to painting a time and place rife with fractious post-colonial tensions, solely a few years earlier than the African territory freed itself from the French Group to change into a fully-fledged republic. However “Pink Island” is a cannier work than that, slowly deromanticizing its purposely naive view of European household life, earlier than sharply jackknifing into a special perspective, even a special movie, altogether.

That swap is each arresting and jarring — a structural pivot that makes for a movie simpler to admire than it’s to embrace. But its autobiographical components are keenly felt, as Campillo grapples intelligently not simply with the blind spots of his private previous, however these of his nationwide heritage. Unexpectedly absent from sure main festivals and met with lukewarm evaluations on house turf, “Pink Island” hasn’t fairly the reassurance or brio of “BPM” or Campillo’s directorial debut “Japanese Boys,” however nonetheless confirms its helmer as a significant identify in up to date French cinema — one who can fill a sprawling interval canvas with appreciable visible creativeness and sensory element.

The movie opens with a disorienting flourish of fantasy: a miniature caper set in a stylized toytown of cardboard and felt, following the crime-fighting exploits of Zorro-masked baby superheroine Fantômette (Calissa Oskal-Ool). It seems these are the vivid imaginings of ten-year-old Thomas (Charlie Vauselle), impressed by his favourite sequence of comedian books; such daydreams recur all through the movie, indicative of a younger thoughts that readily drifts from actuality. Nonetheless, there’s journey and intrigue aplenty in Thomas’ on a regular basis life, which performs out, in any case, on a tropical African island removed from his homeland. He simply must know the place to search for it — when, aping Fantômette, he begins his personal nighttime investigations.

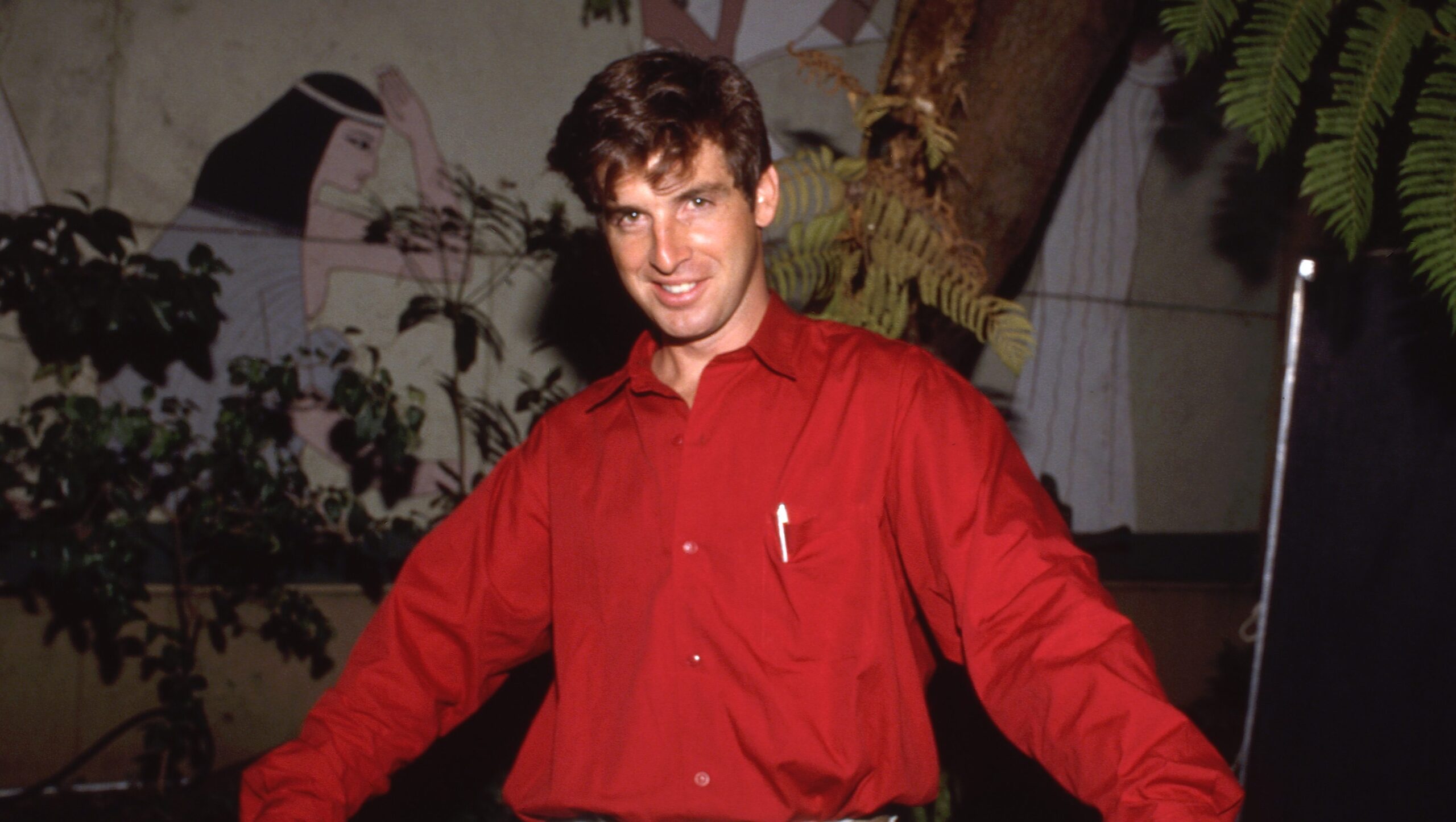

Thomas’ suave military officer father Robert (Quim Gutiérrez, radiating Belmondo-esque allure) and his mom Colette (Nadia Tereszkiewicz) aren’t overly involved with their son’s exploits, parenting him and his siblings in vaguely permissive style. They’re largely distracted by strains in their very own marriage, as Colette begins to doubt her husband’s constancy. As properly she would possibly. An air of blasé sexual liberty permeates the bottom, the place troopers frequent a brothel staffed by native Malagasy girls — one in all whom, Miangaly (Amely Rakotoarimalala), turns into an object of obsessive want for brand new, married recruit Bernard (Hugues Delamarlière). Thomas’ nocturnal snooping turns up no comic-book crime, but it surely does make him an uncomprehending witness to such fragments of grownup mischief.

Campillo sensitively captures the following transition between infantile fancy and disillusionment, which dovetails neatly with the Frenchmen’s apathetic shedding of colonial beliefs — their days there are numbered, and everyone seems to be ready for the following chapter of their lives to start. Not so passive are the Malagasy, restlessly reaching for his or her imminent independence, and backgrounded within the movie till Miangaly seizes narrative focus in a denouement that facilities her folks’s revolution. In the meantime, the white characters we hitherto assumed have been the collective topic are forged into the margins. It’s a stark, pointed shift that may divide audiences: It’s arduous to not want Miangaly’s character had been extra richly developed in parallel with the others all through, although the symbolic affect of her tardy takeover is obvious.

There’s a touch of self-effacement in Campillo’s demotion of his personal coming-of-age story, an acknowledgement of the smallness of his recollections relative to the island’s personal seismic story of the time, even when the movie by no means fairly offers itself over to extra radical concepts. But the household scenes nonetheless carry weight and pathos, as Thomas regularly tunes into his mom’s suppressed unhappiness, and Robert’s alpha paternal gestures (together with, most bizarrely, a present to his kids of child crocodiles) tackle a near-nihilistic desperation. DP Jeanne Lapoirie shoots the burnt-orange Madagascan days and the humid, inky nights with equally saturated depth, making it an applicable backdrop for feelings operating scorching and bothered on all sides. Campillo’s recall might have advanced and matured, but it surely clearly hasn’t light.

The post Robin Campillo’s Evocative Reminiscence Piece appeared first on Allcelbrities.